Why the regional food system needs to change

This section captures background information about how health, money and the natural environment are tied together through what we eat and how we produce it.

Social and Environmental Factors

These data of the Wellington region provide insights into what limits people’s access to good food and how that may influence their health.

Available data is limited, highlighting urgent need for more work and better data about:

Who can't access the food they need to be healthy

Why that is

How we can work together to change it

When we will know that food security is improving

-

In Aotearoa, people have unequal access to resources and opportunities, which strongly influences the health and wellbeing of individuals, whānau and communities. For example, education often affects employment, employment usually relates to income and the food you can afford to choose depends on money available in the household.

Over a lifetime these factors interact and reinforce each other affecting how ‘well’ we are throughout our lives, how quickly we can bounce back after big challenges and how long we live.

The food we eat is also closely linked to food prices, and what food is on offer or marketed around our neighbourhood. Lots of food is bought from supermarkets, and the lack of competition in that sector has not been working well for consumers nor many small food suppliers.

By looking at who makes up the diverse communities in our region and the challenges they have to access the food they need to be healthy, we can work out how the food system might be planned better to meet everyone’s needs.

By improving connectivity between growers, producers and consumers across the region we will grow a food resilient region where everyone has access to good food. By enabling and fostering food security, we can maximise opportunities for our people to live well, to be socially connected, to share resources, to access employment. Importantly, we support our people to prosper.

There are many small medium and large food producers across the region. Supportive policies could amplify the potential for local food to be produced and consumed in our region - creating a resilient regional food economy.

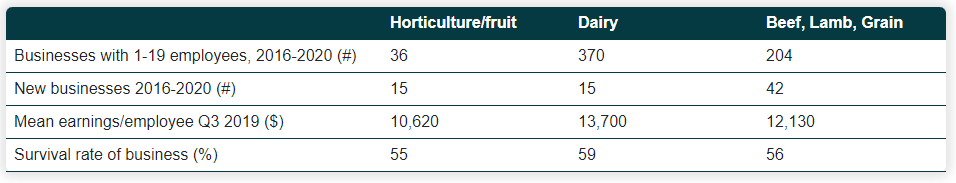

Table 1: Food producers in the Wellington region

There are large tracts of productive land in the Wairarapa and Kapiti Coast areas. There are significant dairy, horticulture and beef and lamb businesses many of which are small and employ a smaller amount of employees compared with city based occupations. The median pay for this work is comparable to median incomes across the region. Councils with a greater proportion of rural land have lower median incomes than those with greater urban density. Urban areas have a greater proportion of women in full-time or part-time employment compared with rural areas.

Although we have large areas of productive land in our region, we are largely reliant on imports from elsewhere in Aotearoa and across the world to stock our supermarket shelves – as evidenced by COVID. Most neighbourhoods are reliant on the supermarket system to provide their food needs. Poorer communities are often reliant on dairies and takeaways. Recent reports from the Commerce Commission suggests that the cost of food to the consumer includes a large profit margin for supermarkets and that the rising cost of food overall is unsustainable for the average consumer. If this money was spent on food produced within the region these profits could be channelled into growing a resilient local food economy.

Nature and health connect through kai:

all life depends on ecosystems to flourish

Nitrogen Phosphorus cycles

Nature has a complicated and delicate system for essential nutrients to move through soil, plants and water. Our food system needs to recognise and work carefully with the natural cycles of these nutrients – nitrogen and phosphorus.

-

Nitrogen Phosphorus cycles

Nitrogen and phosphorus are essential nutrients which plants need to grow. Livestock manure and synthetic fertilisers from farming intensification are major sources of disruption to these nutrient cycles. From 1990-2019, the use of synthetic nitrogen fertilisers increased by 520%.

Too much nitrogen and phosphorus is polluting our rivers and streams. This is causing problems such as overgrowth of algae and makes the waterways less able to support plants and fish. Excess nitrogen can contaminate drinking water and is also an important source of greenhouse gas emissions. Adapting our food production systems to pay closer attention to the natural balances in our environment will mitigate climate change, preserve our freshwater species and mahinga kai – such as koura (freshwater crayfish) and tuna (eels). Producing food more sustainably will also improve the quality of our rivers and streams for swimming, fishing and other enjoyable activities.

Freshwater use

We need freshwater for our food to grow, so our food systems must protect Te Mana o Te Wai (the health and mauri of our water).

-

Freshwater use

Crops, vegetables, grass and livestock all depend on a reliable source of water. Food production, especially in dryer areas, often needs water irrigation to improve yields. In Aotearoa New Zealand, 58% of consented freshwater allocation is for irrigation. However, irrigation can increase the flow of nitrogen and contaminants into rivers and streams, and takes large amounts of water which changes the natural flows of the waterways. These effects are degrading our freshwater sources and harming habitats, aquatic life and taonga species which are important food sources such as īnanga (whitebait). Taking too much groundwater near coastal areas can also draw salt water into drinking water supplies. Climate change is affecting water cycles too, through changes to rainfall, drought and flooding.

Livestock for the production of dairy and meat products have increased the demand for water significantly. Between 2002 and 2017 the area of irrigated agricultural land in Aotearoa New Zealand nearly doubled. Dairy farming accounted for 59% of irrigated land, other livestock 17% and plant foods 24%. The current evidence is uncertain about how much water is actually taken or the full effects on river health, but robust research shows that shifting our global eating patterns to consume less animal products and more plant foods is needed to achieve sustainable water use.

For our food systems to be resilient we must carefully consider how we want to use our precious freshwater resources, as our health is interconnected with Te Mana o Te Wai.

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Our food systems and our Earth’s climate are delicately intertwined - they depend on each other. The way we eat and produce food must change to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, or the land may not be able to provide us with the food we need to sustain and nourish us. Most of what we eat needs to be plant foods.

-

Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Greenhouse gas emissions are the main drivers of climate change. Did you know that a quarter of all global greenhouse gas emissions are generated in food production, processing and distribution? This means that our food system is a key place to look for climate action.

However, our ability to grow crops and raise livestock is threatened by climate change effects such as more frequent extreme weather such as drought or floods. Further rises in global temperatures are likely to reduce freshwater supply, weaken soils, affect pollination and increase risk of crop damage from pests and diseases. There is a risk that food production would be seriously affected and secure access to a healthy variety of foods would be compromised. This food insecurity is more likely to affect people in our population who are already disadvantaged.

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the agriculture sector is responsible for 50% of greenhouse gas emissions, mainly from the production of dairy products, beef and lamb. The main gases produced are methane (from the digestive processes of cows and sheep), nitrous oxide (from synthetic fertilisers) and carbon dioxide (from soil disturbance, food processing and transport). Adopting a plant-based diet would therefore not only reduce greenhouse gas emissions but also is much healthier for most people. Changing farming practices, choosing fresh minimally processed foods and eliminating food waste will also make a big difference

Topsoil Loss and Degradation

To grow kai into the future we need to care for our soil. The way we produce food needs to take a long-term view which recognises that soil health is fundamental to sustain productivity, and the benefits which that brings for food security and for the economy.

-

Topsoil Loss and Degradation

Healthy soil is a vital foundation for our food system. For crops to grow well the soil needs to be of high quality, with the right amount of nutrients and a complex functioning ecosystem of microorganisms. Intensive farming, irrigation, excess fertiliser and pesticide use can all disrupt the soil balance and risks harming the health of the soil. Over the last 20 years in New Zealand there has been a significant increase in irrigated land area and nitrogen fertiliser use has more than doubled. Soil quality indicators indicate excess application of both nitrogen and phosphorus fertiliser in many areas.

New Zealand relies on a relatively small amount of suitable land for food production. Erosion can lead to loss of topsoil from this land. Topsoil is irreplaceable and vital for growing grass and crops. Reduced productivity from soil erosion also creates a demand for nutrients to be added in the form of fertiliser, which can have other negative effects on the environment particularly when it leaches into waterways. Erosion has increased due to land use conversion from native cover to exotic grassland pasture, which supports the production of dairy and meat. This is because livestock can compact the soil and rain runs off pasture more easily. Extreme weather events due to climate change are expected to increase erosion.

A secure and resilient food supply demands that our precious lands and soils are cared for in a way which supports and regenerates natural ecosystems.

Biodiversity and Food production

To grow kai we need our intricate ecosystem of living organisms to all be working together: loss of biodiversity threatens our future food supply. Biodiversity in all our environments is in decline.

-

Biodiversity and Food production

Biodiversity is the range and variety of different living organisms which work together in an ecosystem to maintain balance and support all life. Humans are just one part of this complex web: our activities can cause disruption which affects the stability of the whole system and therefore can impact back on our health and wellbeing. When ecosystems are more biodiverse they are more resilient to disturbances.

Our food supply depends on biodiversity for example in the micro-organisms which regenerate soil and the insects which pollinate plants. Growing a diverse range of crop species provides an important range of nutrients for a healthy diet and creates more resilience for our food supply against pests or climate changes. Biodiversity within our land and water ecosystems supports taonga species such as tuna (eels) and enables mahinga kai (food gathering).

However, food production is also the main driver of biodiversity loss and species extinction. This happens through land conversion to agriculture, which reduces the natural habitats for species and is often focussed on a narrow range of crops or breeds. Intensified food production affects land and freshwater biodiversity through irrigation, synthetic fertiliser and pesticides. Unsustainable harvest of fish and seafood affects marine biodiversity.

Global food systems tend to drive large scale production which focusses on cost and short-term outcomes rather than environmental sustainability and nutritional benefit. Our future health depends on re-orienting our food system to support local producers and communities to grow healthy kai in a way which understands the importance of biodiversity for long term sustainability.

Land use change

The best lands and soils for food production are a life-supporting resource. They need to be protected so that our rights to a variety of healthy kai are prioritised against other pressures on land. A local food supply provides resilience to global disruptions.

-

Land use change

Land which is suitable for growing food (versatile or highly productive land) is a scarce and valuable resource, comprising only 15% of New Zealand’s total land area. Highly productive land is increasingly being fragmented, sold as lifestyle blocks or converted for urban use. Once topsoil has been cleared for building if cannot be replaced and returned to food production later. If current trends continue, a large proportion of highly productive land could be urbanised within 50-100 years. This would affect agriculture exports and diminish the food security of our local population.

Our food needs should be prioritised when making land-use decisions, so that local communities are able to access a variety of healthy kai into the future. Smart urban planning and development strategies are key to meeting our housing needs without encroaching further on highly productive lands.